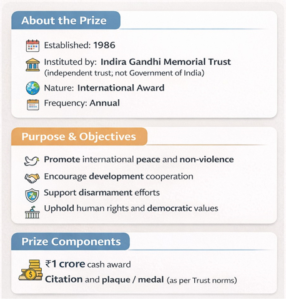

1. Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development 2025

GS paper II-IR

Context :Mozambican activist Graça Machel is currently in the news because she has been awarded the 2025 Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development. The announcement was made on January 21, 2026.

Who is Graça Machel?

- She is a renowned Mozambican politician and humanitarian.

- She is the only woman to have been First Lady of two nations (Mozambique and South Africa).

- Machel served as Mozambique’s first Minister of Education and Culture.

- She is a founding member of “The Elders” and “Girls Not Brides.”

- She is the widow of Samora Machel and Nelson Mandela.

- Her 1996 UN report on children in war changed global humanitarian policy.

Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development

Selection Process

- The Jury: Selection is made by an international jury of eminent personalities.

- Jury Chair: The current 2025 jury was chaired by former NSA Shivshankar Menon.

- Nominations: Proposals come from past winners, MPs, and international organizations.

- Criteria: Based on “path-breaking work” and creative efforts for human good.

- Final Decision: The Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust announces the final winner annually.

- Presentation: The prize is typically presented by the President of India.

2. Rajasthan “Disturbed Areas” Bill, 2026.

GS paper III-polity

CONTEXT :Rajasthan Cabinet cleared the Rajasthan “Disturbed Areas” Bill, 2026.

- It empowers the State to declare areas as “disturbed” amid communal violence, distress sales, and alleged demographic shifts.

Key Terms

- Disturbed Area: Area notified by State due to communal violence, riots, or serious public disorder.

- Distress Sale: Forced property sale at throwaway prices due to fear or coercion.

- Immovable Property: Land, buildings, and property permanently attached to land.

- Competent Authority: District Collector / District Magistrate, who grants prior permission.

About the Bill

- Full name: Rajasthan Prohibition of Transfer of Immovable Property and Provisions for Protection of Tenants from Eviction from the Premises in Disturbed Areas Bill, 2026.

- It is a State legislation, modelled on Gujarat’s Disturbed Areas Act.

Salient Provisions

- State government can declare any area as “disturbed” on grounds of communal violence, riots, mob unrest, or improper clustering linked to demographic change.

- Transfer of any immovable property in such areas requires prior permission of the Competent Authority.

- Any transfer without permission is null and void.

- Eviction of tenants from premises in disturbed areas is barred without following due process.

- Violations are cognisable and non-bailable; punishment is 3–5 years jail and fine.

- Declaration is valid for one year and can be extended periodically.

Rationale / Government’s Argument

- To prevent forced displacement of residents during communal tensions.

- To curb distress sale of property at undervalued prices.

- To preserve communal harmony and social structure.

- To protect economically weaker residents from exploitation.

Criticism / Issues

- Term “demographic imbalance” is not legally defined.

- Law gives wide discretionary powers to the bureaucracy.

- May violate the right to property (Article 300A) and freedom of trade.

- Risk of selective or politically motivated application.

- May discourage investment and real estate activity in notified areas.

Constitutional & Legal Dimensions

- Public order is a State subject (List II, Seventh Schedule).

- Right to property is not a fundamental right but is protected under Article 300A.

- Law may face judicial scrutiny on grounds of reasonableness, arbitrariness, and proportionality.

Comparison with Other States

- Gujarat has a similar law: Gujarat Disturbed Areas (Acquisition of Immovable Property) Act, 1986 (amended in 2020).

- Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh have had earlier laws on disturbed areas or similar concepts.

3. Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI)

GS PAPER III-ECONOMY

Context :The Union Cabinet has approved an equity infusion of ₹5,000 crore into the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) to boost institutional credit for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs).

Key Terms

- Equity Infusion: Government’s capital injection to strengthen a financial institution’s balance sheet and capital base.

- MSMEs: Enterprises categorized under the MSMED Act, 2006, based on investment and turnover.

- CRAR: Capital to Risk-weighted Assets Ratio – a measure of a bank’s capital adequacy relative to its risk-weighted assets.

About SIDBI

- Status: The principal development financial institution (DFI) for the MSME sector in India.

- Established: 2 April 1990.

- Governing Law: Set up under the Small Industries Development Bank of India Act, 1989.

- Headquarters: Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh.

- Mandate:

- Promote, finance, and develop MSMEs.

- Strengthen and facilitate the flow of credit to MSMEs.

- Address financial and developmental challenges in the MSME ecosystem.

- Coordinate the activities of institutions involved in MSME financing.

- Ownership: Jointly owned by the Central Government and 29 other entities, including Public Sector Banks (PSBs) and Central Government-owned insurance companies.

- Administrative Control: Overseen by the Department of Financial Services, Ministry of Finance.

Rationale for the Equity Infusion

- Enhance Capital to Risk-Weighted Assets Ratio (CRAR) and overall balance sheet strength of SIDBI.

- Support growth in risk-weighted assets (RWA) to enable larger lending.

- Increase the availability of affordable and timely credit to MSMEs.

- Help bridge the persistent credit gap faced by small enterprises.

4. Saltwater crocodile

GS paper III-Environment

Context :The population of saltwater crocodiles in Odisha’s Bhitarkanika National Park rose to 1,858 in 2026.

- A recent survey across the Ganga River basin revealed a population of 3,037 gharials.

- New pilot drone-based surveys were introduced in 2026 to estimate crocodile numbers.

Habitat & Distribution

India

- Saltwater Crocodile: Found in Bhitarkanika (Odisha), the Sundarbans (West Bengal), and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

- Gharial: Survives in the Chambal, Girwa, Son, Gandak, Ramganga, and Mahanadi rivers.

- Mugger Crocodile: Widespread in freshwater lakes, rivers, and marshes across most of India.

Others (Global)

- Saltwater Crocodile: Extends from Southeast Asia to Northern Australia and Micronesia.

- Gharial: Historically spanned Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, and Pakistan, but now restricted to India and Nepal.

Protection Status

- IUCN Red List: Saltwater crocodiles are Least Concern, while Gharials are Critically Endangered.

- Wildlife Protection Act (1972): Both are listed under Schedule I, granting them the highest legal protection in India.

- CITES: Both species are listed in Appendix I, strictly regulating international trade.

About Gharials & Types

- Classification: Gharials belong to the family Gavialidae, distinct from other crocodiles and alligators.

- Types: There are two living species in this family: the Gharial and the False Gharial (Tomistoma).

- Diet: They are primarily fish-eating reptiles, using their specialized snouts to catch slippery prey.

Physical Characteristics of Gharials

- Snout: Characterized by an extremely long and thin snout containing about 110 interlocking teeth.

- The “Ghara”: Adult males have a bulbous growth at the snout tip, named after the Indian earthen pot (ghara).

- Size: Males are among the longest crocodilians, reaching up to 16–20 feet in length.

- Aquatic Adaptation: Most aquatic of all crocodilians; they have weak leg muscles and move poorly on land.

- Coloration: Typically olive-colored or light brown, turning darker/black as they age.

5. Aravalli Range

GS PAPER I-GEOGROAHY

Context :The Supreme Court of India has suggested the formation of a multi-disciplinary expert committee to scientifically demarcate the Aravalli Range and lay down a roadmap for permissible activities, including regulated mining, under the Court’s supervision.

Importance of Defining the Range

- Determines the areas under mining restrictions and those where exploration/operations may be permitted.

- Affects the grant of environmental clearances and the extent of regulatory oversight.

- Decides where court orders, conservation norms, and green laws apply to protect the range.

Controversy

There are concerns that the proposed draft definition (e.g., protecting only hills above 100 metres) could leave large tracts of the Aravalli unprotected, making them vulnerable to mining and environmental degradation.

About the Aravalli Range

Age and Type

- One of the oldest fold mountain systems in the world, formed during the Proterozoic era.

- Forms part of the Aravalli–Delhi Orogenic Belt within the Indian Shield.

Orientation and Extent

- Runs roughly south-west to north-east for about 670–700 km, passing through:

- Delhi

- Haryana

- Rajasthan

- Gujarat (near Ahmedabad).

Relief and Topography

- Made up of discontinuous ridges, hillocks, and residual mountains, not a continuous chain.

- Highest peak: Guru Shikhar (1,722 m / 5,650 ft) at Mount Abu, the tallest point in the Aravalli Range.

Physiographic Role

- Acts as a climatic and hydrological barrier, separating the arid north-western Thar region from the relatively fertile plains in the south-east.

Drainage and Watershed

- Serves as a major drainage divide:

- Western slopes: Feed rivers like Luni and Sabarmati, flowing towards inland/arid zones and the Arabian Sea.

- Eastern slopes: Feed the Chambal–Banas–Berach basins, which are part of the larger Yamuna river system.

- Characterised by seasonal rivers and paleochannels (ancient river channels).

Geology

- Dominated by Archean gneiss, schist, quartzite, and marble; heavily eroded over geological time.

Mineral Significance

- Forms one of India’s oldest mineral belts, rich in:

- Copper

- Zinc

- Lead

- Marble.

Ecological and Historical Value

- Checks the eastward expansion of the Thar Desert.

- Supports:

- Wetlands and groundwater recharge.

- Diverse biodiversity and habitats.

- Hosts Indus Valley and OCP (Late Harappan) archaeological sites along the Luni–Sahibi systems.

6. Should corruption charges need prior sanction ?

GS paper II-Governace

CONTEXT :A Supreme Court 2-judge bench split on the validity of Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption Act.

- Judicial opinion divided: Justice B.V. Nagarathna struck it down; Justice K.V. Viswanathan upheld it.

- Matter referred to a larger 3-judge bench for final decision.

Legal Challenge under Section 17A

- CPIL challenged Section 17A, arguing it gives a special shield to corrupt officials.

- It is said to violate Article 14 (Right to Equality) by creating differential treatment.

- Prior government approval is needed before any investigation into an officer’s official acts.

Purpose of Section 17A (2018 Amendment)

- Introduced in 2018 to protect honest officers from malicious or frivolous investigations.

- Aims to prevent “policy paralysis” due to fear of arbitrary probes.

- Requires prior approval before any inquiry or investigation into official decisions or recommendations.

Divergent Judicial Opinions

Justice B.V. Nagarathna (Against 17A)

- Held Section 17A violates Article 14 by creating a privileged class.

- Said it defeats the main purpose of the PCA, which is to punish corruption.

- Called it a “barrier at the threshold” to corruption investigations.

- Noted it is similar to earlier invalidated provisions, like Section 6A of the DSPE Act.

Justice K.V. Viswanathan (In Favour of 17A)

- Held Section 17A is constitutionally valid as a functional necessity.

- Argued it is needed to prevent honest officers from adopting a “play-it-safe” approach.

- Suggested “reading down” the law so approval is given by Lokpal/Lokayukta, not the Executive.

- Warned that striking it down completely would hurt administrative efficiency.

Way Forward

- The split verdict means the question is now before a 3-judge bench.

- The larger bench will decide whether Section 17A is constitutional or not.

- Goal: balance protection of honest officials with free and fair investigation of corruption.

7. Judicial removal -tough law with a loophole

GS II-polity

Context :A recent impeachment notice moved in Parliament against a High Court judge has once again spotlighted India’s judicial removal mechanism.

- The debate has intensified on whether the current procedure, especially the power of the Speaker/Chairman to admit or reject an impeachment motion, is sufficient to ensure accountability of judges without compromising judicial independence.

Constitutional Basis for Judicial Removal

- Judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts can be removed only through a parliamentary process under Articles 124(4), 124(5), 217(1)(b) and 218 of the Constitution.

- The process is commonly called “impeachment” in popular discourse, even though the Constitution uses the term “removal”.

- Article 124(5) specifically empowers Parliament to make a law regulating the procedure for the presentation of an address, and for investigation and proof of the misbehaviour or incapacity of a judge.

Grounds for Removal

- A judge can be removed only on the grounds of “proved misbehaviour or incapacity”.

- “Misbehaviour” is not defined in the Constitution but has been interpreted by courts to include:

- Wilful misconduct and corruption.

- Abuse of judicial office for personal gain.

- Conduct that brings dishonour or disrepute to the judiciary.

- Conviction for offences involving moral turpitude or serious ethical lapses.

The Procedure for Removal

- An impeachment motion must be passed by each House of Parliament with:

- A majority of the total membership of that House.

- And a two-thirds majority of members present and voting.

- After both Houses pass the motion, the address is presented to the President, who then issues an order for the judge’s removal.

- Parliament has used this power to make the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 and the Judges Inquiry Rules to regulate the detailed procedure.

The Impeachment Motion Process

- A motion for removal must be introduced through a notice signed by at least 100 members of Lok Sabha or 50 members of Rajya Sabha.

- The Speaker of Lok Sabha or the Chairman of Rajya Sabha decides whether to admit or disallow the motion.

- If admitted, they appoint an Investigation Committee consisting of:

- A sitting Supreme Court judge.

- A Chief Justice of a High Court.

- A distinguished jurist.

- The Committee conducts a quasi-judicial inquiry, gives the judge a chance to be heard, and submits a report on whether the charge is proved.

Parliamentary Stage and Removal

- If the Committee finds the charges of misbehaviour or incapacity proved, the motion for removal is taken up in both Houses of Parliament.

- The motion is debated and then put to vote in each House.

- Only if both Houses pass it with the prescribed majority is the President empowered to issue the removal order.

- Till date, no Supreme Court judge has been removed through this process; in the High Courts, only a few motions have been initiated.

Powers of the Speaker/Chairman and the Controversy

- The Speaker/Chairman has the authority to decide whether the motion is admissible or not, based on prescribed rules and legal standards.

- This power has been criticised as giving excessive discretion that can be misused to block legitimate motions, especially if the government seeks to protect a politically inconvenient judge.

- Critics argue that this provision creates a loophole, allowing the executive and the presiding officers to frustrate the constitutional mechanism for holding judges accountable.

- Since there are no clear statutory criteria or time limits for deciding on admissibility, the process risks becoming opaque and subjective.

Need for Revisiting the Procedure

- The discretion of the Speaker/Chairman should be better defined and limited by law or rules to ensure judicial accountability.

- Time-bound procedures must be laid down to prevent indefinite pending or silent rejection of motions.

- The role of the presiding officers should be limited to verifying formal compliance rather than acting as gatekeepers of substantive allegations.

- A more transparent, institutional mechanism (e.g., a standing committee of members) could be considered to recommend whether a motion should proceed, reducing arbitrariness.

Conclusion

- The Constitution provides a strong but narrow ground for judge removal: “proved misbehaviour or incapacity,” with a stringent parliamentary majority requirement.

- However, the current procedure, particularly the wide discretion of the Speaker/Chairman, risks undermining this constitutional safeguard.

- To balance judicial independence with accountability, there is a pressing need to reform the impeachment process so that serious allegations are not thwarted by procedural discretion, and the system remains insulated from political manipulation.

8. Lowering the age of Juvenility for crimes is a step back

GS paper II-POLITY, Governance

Context :A Private Member’s Bill introduced in Parliament in December 2025 seeks to amend the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

- The Bill proposes to lower the age threshold for trial as an adult in heinous offences, from 16–18 years to 14–18 years.

- This has reignited the national debate on whether children should be treated as adults for heinous crimes or the focus should remain on rehabilitation.

Current Law: Juvenile Justice Act, 2015

- For children aged 16–18 accused of a “heinous offence” (punishable with 7 years or more), the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) conducts a preliminary assessment.

- If the JJB concludes that the child has the mental capacity and maturity of an adult, that child can be tried as an adult and sent to a place of safety for up to 3 years after turning 21.

Core Proposal of the 2025 Bill

- The Bill seeks to extend the “adult trial” provision to children aged 14–16 years as well.

- Children in this age group, if found capable of adult judgment, may be tried in regular courts and potentially placed in adult-like detention facilities after 21.

- The intent cited is stricter deterrence for serious crimes committed by older minors.

Criticisms of the Proposed Lowering of Age

- The “Transfer System” Is Already Flawed

- The current system to decide whether a 16–18-year-old should be tried as an adult is seen as vague and arbitrary.

- No standardized or scientifically validated tools exist to reliably assess whether a child has “adult-like capacity” at the time of the crime.

- Outcomes often depend on the subjective opinion of the JJB, leading to unequal treatment of children with similar circumstances.

- Treating 14-Year-Olds as Adults Is Developmentally Inappropriate

- At 14, children are still in early adolescence, with underdeveloped impulse control, risk assessment, and emotional regulation.

- International norms (e.g., UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) treat 18 as the age of adulthood and discourage trying children in adult courts.

- Bringing 14-year-olds into the adult system erases the crucial distinction between childhood and adulthood in law.

- Harmful Consequences of Adult Prisons

- Placing adolescents in adult-like prisons interrupts their education and normal cognitive and social development.

- The punitive environment increases psychological trauma, stigma, and the risk of long-term recidivism.

- Studies show that harsh treatment in adulthood-focused systems makes juveniles more likely to re-offend, undermining public safety.

- Prioritizes Retribution Over Rehabilitation

- The move is seen as focusing on punishment and retribution rather than addressing the root causes of youth crime.

- It shifts the burden onto the child, while ignoring systemic failures in family support, education, and mental health services.

- Juvenile justice, in principle, is meant to reform and reintegrate, not to punish as in the adult system.

The Way Forward: A Systemic Approach

- Reject Retribution: The law should not further blur the line between adolescence and adulthood; it must respect the special status of children.

- Invest in Prevention: Greater resources should go to early intervention, counselling, school-linked support, and strengthening families.

- Reform the System: Fix the flaws in the JJB and the “transfer” system instead of lowering the age for adult trials.

- Holistic Accountability: The state must be held accountable for failing to protect children and create safe environments, rather than punishing children more harshly.