1. GI tag push for traditional items reshapes Bodoland poll narrative

GS Paper III: Economic Development: Intellectual Property Rights (IPR), GI tags, and their role in promoting economic growth, rural development, and export potential.

GS Paper II: Governance and Social Justice: Policies and interventions for the protection of indigenous communities and their cultural heritage;

Context: Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) in Assam is election-bound (polls on September 22, 2025).

- A major poll-time discussion is the push for Geographical Indication (GI) tags for traditional products, crafts, textiles, food items, and medicinal plants.

- So far, 21 items secured GI registration (2023–24), with more items under process.

What is a GI Tag?

- Geographical Indication (GI) tag: A legal recognition that a product originates from a particular region and has qualities, reputation, or uniqueness linked to that place.

- Benefits:

- Protects against imitation/unauthorised use

- Boosts market value and exports

- Preserves cultural heritage

- Ensures consumer trust in authenticity

- Aids rural livelihood and development

| Background

Origin of the Bodo Tribe.

Constitutional Provisions

The Bodo Peace Accord (2020), also called the Third Bodo Peace Accord, was signed on January 27, 2020, between the Government of India, the Assam state government, and major Bodo groups including the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) and the All Bodo Students’ Union (ABSU). Objectives

Key Provisions

Achievements

|

Key Developments in BTR

GI Tag Initiative: A group of Bodo youth—biotechnologist Ling Narzihary, artist Swapna Muchahary, social worker Kansai Brahma, and entrepreneurs Nachani Brahma, Pulak Basumatary, and Ranjila Mohilary—started work in 2021 to document traditional heritage.

- They identified over 50 items, with 21 products securing GI tags between November 2023 and May 2024.

- The initiative is aimed at:

- Preserving Bodo heritage

- Preventing cultural appropriation

- Creating opportunities for economic growth

BTR Government’s Role: The BTR government, led by Chief Executive Member Pramod Boro (UPPL), made indigenous heritage recognition a priority after the 2020 Bodo Peace Accord.

- A special GI-tag drive was launched to cover items from all 26 communities in the region.

- Collaboration with the Gandhi Hindustani Sahitya Sabha (Delhi) brought expert workshops to guide communities in identifying and documenting cultural assets for GI applications.

Future Plans: Establishment of GI Villages to support artisans and farmers with:

- Training

- Infrastructure

- Direct market linkages

- A major Authorised Users (AU) registration campaign under the Chief Executive Member’s Special Initiative Scheme, targeting 100,000+ artisans, farmers, and weavers, with mobile app support for easy registration.

- Development of a Bodo Heritage Park to:

- Showcase GI products

- Create employment opportunities

- Strengthen revenue generation and sustainability

Political Context

- The GI push is rooted in a 2010s ABSU resolution under then-president Pramod Boro.

- Boro, now Chief Executive Member, leads the UPPL government in alliance with the BJP and Gana Suraksha Party.

- In the upcoming elections, they face a three-way contest against the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF).

- The GI-tag movement has emerged as a key poll issue, reframing the discourse around cultural identity and economic empowerment.

Communities Involved

- Bodos (dominant group) and 25 other communities including:

- Adivasis

- Gurkhas

- Koch-Rajbongshis

- Hajongs

- Kurukhs

- Madahi Kacharis

- Hiras

- Patnis

Examples of GI-tagged Items (21 so far)

- Textiles: Aronai, Dokhona, Zwmgra

- Musical Instruments: Kham, Serza, Siphung

- Alcoholic Beverages: Maibra Zwu Bidwi, Zwu Gisi

- Cuisine: Gwkha Gwkhwi, Napham

- Medicinal Plants: Gongar Dundia, Khera Daphini

The GI tag initiative in Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) goes beyond cultural recognition; it is a powerful strategy for economic empowerment, especially for women in handloom weaving and organic farming. By legally protecting traditional knowledge and improving access to markets, this initiative is transforming BTR into a model region where cultural heritage serves as a foundation for sustainable development and gaining global recognition.

2. Blood Moon’ and Lunar Eclipse

GS Paper I Geography : Important Geophysical Phenomena

Why in News?

- A rare total lunar eclipse, also called a Blood Moon, occurred overnight on September 7–8, 2025.

- It was visible across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia, captivating millions of skywatchers worldwide.

- The eclipse lasted about 82 minutes, making it one of the longest total lunar eclipses in the past decade.

Background of the September 2025 Eclipse

|

About Lunar Eclipse

- A lunar eclipse happens when the Earth moves directly between the Sun and the Moon, casting a shadow on the Moon.

- During a total lunar eclipse, the Moon passes completely through Earth’s dark central shadow called the umbra.

- Instead of the Moon appearing dark, Earth’s atmosphere bends sunlight, scattering blue light and allowing red wavelengths to illuminate the Moon, giving it a characteristic red or coppery glow known as the Blood Moon.

Why Lunar Eclipses Don’t Occur Every Month

- The Moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5 degrees relative to Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

- Because of this tilt, the Moon usually passes above or below the Earth’s shadow during full moons, preventing an eclipse every month.

- Lunar eclipses only occur when the Sun, Earth, and Moon are precisely aligned near the points where these orbital planes intersect.

What is a Blood Moon?

- The term refers to the reddish appearance of the Moon during a total lunar eclipse.

- The red color results from sunlight filtering through Earth’s atmosphere, similar to the hues seen during sunrises and sunsets.

- This atmospheric effect causes the Moon to glow with a deep, dramatic red shade, creating an eerie and beautiful spectacle.

Significance

- Lunar eclipses have fascinated humans for millennia, often embodying themes of mystery, change, and transformation in cultures worldwide.

- Astronomically, such eclipses offer valuable opportunities for studying the Earth-Moon-Sun system.

- Modern scientific societies and skywatchers use eclipses for observation, photography, and educational outreach.

- The 2025 eclipse is especially significant due to its long duration and wide visibility, uniting billions in a shared celestial experience

3. Katchatheevu island

GS Paper II: International Relations: India-Sri Lanka bilateral relations, maritime boundary disputes, and regional cooperation in the Indian Ocean region.

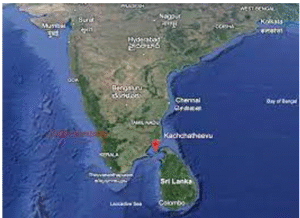

Context: In September 2025, Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake made a historic visit to Katchatheevu island, the first by a Sri Lankan head of state, reaffirming Sri Lanka’s sovereignty.

- Indian politicians, especially in Tamil Nadu, have revived demands to reclaim Katchatheevu amid upcoming state polls.

- The dispute remains a sensitive issue tied to fishery conflicts and political rhetoric despite being diplomatically settled decades ago.

Historical Background

- Katchatheevu is a 1.15 sq. km uninhabited island in the Palk Strait, located about 33 nautical miles off the Jaffna Peninsula (Sri Lanka) and near Tamil Nadu coast.

- Owned historically by the Madras Presidency (British India) but remained disputed until the 1970s.

- In 1974 and 1976, India and Sri Lanka signed bilateral agreements recognizing Katchatheevu as Sri Lankan territory to settle long-standing maritime boundary disputes.

- India received sovereign rights over Wadge Bank near Kanniyakumari in exchange.

Geographical Location

- Situated in the Palk Strait, between Tamil Nadu (India) and Jaffna Peninsula (Sri Lanka).

- The island is barren, without fresh water or sanitation facilities.

- It hosts the St. Anthony’s Catholic Shrine, a pilgrimage site for both Indian and Sri Lankan fishermen annually.

Importance of Katchatheevu

- Strategic Location: Katchatheevu lies in the Palk Strait, a key maritime corridor connecting the Bay of Bengal with the Gulf of Mannar and the broader Indian Ocean.

- Its location is vital for maritime security and monitoring naval activities in this busy sea route.

- Fishermen Dispute :Tamil Nadu fishermen regard Katchatheevu as their traditional fishing ground.

- Sri Lankan authorities often arrest Indian fishermen for entering waters around the island, leading to diplomatic tensions and protests in Tamil Nadu.

- Religious and Cultural Significance :The island houses the St. Anthony’s Catholic Shrine, a site of religious importance for Catholic fishermen from both India and Sri Lanka.

- Indian pilgrims are granted visa-free access annually to participate in the festival at this shrine.

- Marine Resources and Economic Livelihoods :The waters surrounding Katchatheevu are abundant in marine biodiversity, including valuable fish species, corals, and sea cucumbers.

- The livelihoods of many fishermen from Tamil Nadu’s Ramanathapuram district heavily depend on these marine resources.

Dispute and Controversy

Tamil Nadu’s Opposition

- Political leaders in Tamil Nadu claim that ceding Katchatheevu to Sri Lanka without parliamentary approval was unconstitutional.

- There are demands to reclaim the island or renegotiate fishing rights to protect fishermen’s interests.

- Several petitions challenging the 1974 agreement have been filed in India’s Supreme Court.

- The Tamil Nadu government asserts that ceding Katchatheevu has adversely impacted the livelihoods of Indian fishermen.

India-Sri Lanka Bilateral Relations

- The dispute continues to strain relations, with frequent arrests of Indian fishermen by Sri Lankan naval forces.

- Sri Lanka contends that Indian fishing practices, especially bottom trawling by Indian fishermen, harm marine ecosystems and threaten local fishing communities.

- Both nations have engaged in talks aimed at resolving these issues, including proposals for joint patrolling and the regulation of fishing practices.

Government Position on Katchatheevu

- The Government of India maintains that sovereignty over Katchatheevu was never definitively Indian prior to the 1974 agreement.

- It asserts that India ceded no territory but formally recognized Sri Lankan sovereignty through bilateral agreements.

- The Indian government emphasizes the impracticality of reclaiming the island, with past statements indicating such efforts would require military conflict.

- India continues to grant visa-free access for religious pilgrimages during the annual festival.

Way Forward

- Continued diplomatic dialogue to uphold friendly India-Sri Lanka ties and address fishermen’s concerns.Enhance bilateral cooperation to phase out destructive fishing practices like bottom trawling.

- Provision of compensation and alternative livelihood options for fishermen affected by the dispute. Promote education for fishermen on maritime boundaries and legal fishing zones to reduce conflicts.

- Political consensus within India to balance regional sentiments with diplomatic realities and sustainable resource management.

4. The vanishing practice of Apatanis

GS Paper I: Indian Heritage and Culture: Preservation of tribal cultural practices, traditional knowledge systems, and their decline due to modernization.

GS Paper II: Social Justice: Impact of government policies (e.g., bans on traditional practices) on tribal communities and their integration into mainstream society.

Context :The Apatani tradition of large wooden nose plugs and facial tattoos is rapidly fading.The practice was banned in the early 1970s and is now mostly seen among older women.

- This tradition, once a protective measure, is a significant cultural identity marker facing modern challenges.

| Background of the Apatani Tribe

Historical Roots

Cultural Evolution

Modern Challenges

|

Who Are the Apatanis?

- Indigenous tribe living in the Ziro Valley, Lower Subansiri district, Arunachal Pradesh.

- The valley is a picturesque, bowl-shaped land in the eastern Himalayas, rich in cultural heritage.

Distinctive Tradition of Apatani Women

- Women wore large wooden nose plugs called yaping hullo, and had facial tattoos termed tippei.

- Originated as a means to protect women from abduction by rival tribes by making them appear less attractive.

- Tattoos were applied by elder women around age 10, using ink made from soot and animal fat.

- Nose plugs made from forest wood were cleaned thoroughly to prevent infections.

Cultural Significance

- The practice evolved into a symbol of beauty, honor, and tribal identity.

- Women wearing these modifications were seen as protectors of family dignity and members of the Apatani tribe.

- The marks signify cultural pride and served as a distinctive feature separating Apatanis from neighboring tribes.

Decline of the Practice

- Government banned nose plugs and facial tattoos in the early 1970s due to social and employment difficulties for women in cities.

- Modern societal changes and urban migration contributed to the decline.

- Now primarily seen only among older generations; younger Apatanis mostly do not follow the practice.

Apatani Tribe – Location & Identity

Location

- The Apatani tribe inhabits the Ziro Valley in the Lower Subansiri district of Arunachal Pradesh.

- The valley is a bowl-shaped plateau, nestled in the lower ranges of the eastern Himalayas, at an elevation ranging from 1,525 to 2,900 meters.

- Ziro Valley is surrounded by pine-covered hills and comprises approximately 32 sq. km of cultivable land within a larger 1,058 sq. km area.

- It is recognized by UNESCO as a tentative World Heritage Site for its exemplary sustainable agricultural practices.

Identity

- The Apatanis are unique among Arunachal tribes for their sedentary lifestyle, unlike the predominantly nomadic neighboring tribes.

- They possess advanced agricultural techniques, vibrant cultural festivals, and maintain a harmonious relationship with nature.

- Traditional village councils called bulyañ govern community affairs and resource management, fostering a strong sense of identity and self-governance.

Festivals

- Dree Festival (July): An agricultural festival where the community prays for harvest success, featuring communal dances like Pakhu-Itu and Daminda, and the distribution of cucumbers symbolizing abundance.

- Myoko Festival (March): Celebrates fertility and ancestor worship, conducted under guidance from Nyibu priests; pine wood plays a key role in rituals, echoing environmental reverence.

- Murung Rituals (January): Involves animal sacrifices to honor gods and promote prosperity and fertility. Folk tales such as Yorda Ayu link the facial tattoos to mythological origins.

- Festivals prominently feature traditional attire, community dances, and rice-millet beer, strengthening social bonds and cultural continuity

Agriculture & Unique Practices

- The Apatanis practice wet rice cultivation, integrating paddy cultivation with fish farming, utilizing nutrient-rich run-off from surrounding hills.

- Their agriculture is sustainable and free from reliance on animals or machinery.

- They maintain sustainable forestry with designated grazing areas, sacred groves, and plantations, protected under customary laws to safeguard forests and irrigation sources.

- Bamboo plays a vital role in daily life, used extensively for housing, crafts, and cooking vessels such as fish steamers.

- Their intricate handloom work, including shawls and jackets, showcases their artistic heritage.

- They possess vast herbal knowledge employed in remedies for both humans and livestock, reflecting deep ecological wisdom.

Conclusion

The disappearing tradition of facial tattoos and nose plugs among the Apatani tribe reflects the broader struggle to preserve indigenous heritage in a rapidly modernizing world. Once serving as protective measures and later embraced as icons of beauty and cultural identity, these practices have nearly vanished due to government bans, social stigma, and evolving aspirations. Nevertheless, the Apatanis continue to distinguish themselves through their sustainable agricultural methods, vibrant festivals, and profound ecological knowledge, which have earned Ziro Valley a place on UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list. As the generation of tattooed women grows older, ongoing efforts to document and celebrate Apatani culture—through education, respectful tourism, and cultural festivals—offer a pathway to bridge tradition with contemporary progress.

5. Parrondo’s paradox

General Studies Paper III : Science and Technology: Advances in medical research, application of game theory in healthcare, and innovative cancer therapies.

- Context: A recent August 2025 study published in Physical Review E applied Parrondo’s paradox to cancer therapy.

- Researchers used mathematical models and simulations to test alternating chemotherapy schedules—maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and low-dose metronomic (LDM)—finding that this combined strategy could better control resistant cancer cells and preserve healthy cells longer compared to either used alone.

- This practical application showcases the paradox’s potential beyond theory, pending real-world clinical trials.

What is Parrondo’s Paradox?

- Originally a concept from game theory and physics, Parrondo’s paradox shows how two losing strategies, when alternated in a specific sequence, can produce a winning outcome.

- A common example is two coin-tossing games that individually lead to losses, but combined in a particular pattern generate net gains.

- The paradox illustrates how mixing “bad” options can sometimes yield “good” results due to interactions and dependencies between strategies.

Background

|

Measures (Application to Cancer Therapy)

- Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD): High-dose chemotherapy administered at spaced intervals, effectively kills most cancer cells but leaves resistant cells which can regrow.

- Low-Dose Metronomic (LDM):Sustained low-dose chemotherapy which prevents tumor growth by anti-angiogenesis and immune modulation but alone may allow resistant or sensitive cells to survive.

- Alternating MTD and LDM: Cycling between the two disrupts cancer cell resistance patterns, prolongs disease control, and better preserves healthy cells, representing a weak form of Parrondo’s paradox in treatment.

How It Works:

- Alternating prevents any single cell type (sensitive or resistant) from dominating, as each schedule targets different aspects of the tumor ecosystem.

- This mimics Parrondo’s paradox: two “losing” strategies (MTD and LDM, each flawed alone) combine to produce a “winning” outcome (delayed resistance, prolonged control).

Challenges

- The alternating therapy strategy needs clinical validation through trials to establish safety, efficacy, and optimal scheduling.

- Cancer heterogeneity and patient variability pose challenges in designing universal alternating protocols.

- Managing side effects and coordinating combination therapies require careful medical supervision.

- Translating mathematical and simulation insights into practical oncological protocols involves multidisciplinary collaboration.

Conclusion:

Parrondo’s paradox, a fascinating concept from game theory, demonstrates how alternating two suboptimal strategies can yield a better outcome. Its application in cancer therapy, as highlighted in the August 2025 Physical Review E study, shows promise in delaying drug resistance by cycling MTD and LDM chemotherapy schedules. While still in the theoretical stage, this approach could transform cancer treatment if validated clinically.

6. The making of an ecological disaster in the Nicobar

GS Paper II: Social Justice: Protection of indigenous communities, particularly Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), and issues of displacement and cultural erosion.

GS Paper III: Economic Development: Infrastructure projects.

Why in News ?

- The Great Nicobar mega-infrastructure project, costing around ₹72,000 crore, is facing criticism for its ecological, social, and legal implications.

- It threatens indigenous tribal communities, endemic flora and fauna, and is vulnerable to natural disasters.

- Despite protests and legal concerns, the project is progressing, raising alarms among environmentalists, tribal rights activists, and some constitutional bodies.

| Background

The Great Nicobar Mega Infrastructure Project is a large-scale development initiative launched in 2021 to transform Great Nicobar Island, the southernmost part of India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands, into a strategic economic and defense hub. Here are the key details: What is it?

Main Components:

|

Issues Raised

Impact on Indigenous Communities

- The Nicobarese and Shompen tribes inhabit Great Nicobar; the project area overlaps their ancestral lands.

- The 2004 tsunami forced their evacuation, and the project threatens to permanently displace Nicobarese, ending hopes of return.

- The Shompen, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG), face risk of losing access to crucial forest areas essential for their survival.

- Legal requirements, such as consulting the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes and local tribal councils, were reportedly ignored.

- A Letter of No Objection obtained under pressure was later revoked by the Tribal Council.

- The Social Impact Assessment (SIA) and Forest Rights Act protections have been inadequately implemented or bypassed.

Environmental Concerns

- The project could lead to deforestation of estimated 15% of the island’s land—8.5 to possibly 58 lakh trees—destroying unique rainforest ecosystems.

- Compensatory afforestation planned in Haryana, far away from the island, is seen as insufficient and ecologically irrelevant.

- Parts of the port site lie within Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) 1A, where construction is banned due to sensitive marine life like turtle nesting sites and coral reefs.

- Independent environmental and wildlife assessments faced methodological flaws and political pressure.

Natural Disaster Risks

- The island is seismically active; the 2004 tsunami caused land subsidence, and a 6.2-magnitude earthquake occurred in July 2025.

- Building large infrastructure here poses heightened risks to lives, property, and long-term investments.

Government Role

- The Government is pushing the project despite protests and legitimate concerns from tribal communities, environmentalists, and some statutory bodies.

- Legal safeguards and consultation processes appear to have been bypassed or rushed.

- Ministries like Tribal Affairs, Environment, and local governance bodies have had limited influence on project halts or revisions.

Importance to India

- Strategic Importance:Strengthens India’s presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), helping counter China’s “String of Pearls” strategy which includes ports in Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

-

- The transshipment port reduces dependency on foreign hubs such as Singapore, which handles about 25% of India’s cargo, supporting India’s Sagarmala initiative to enhance coastal shipping.

- Economic Benefits:Expected to generate revenue of around ₹1 lakh crore over 30 years.

-

- Creates employment opportunities and boosts tourism in the remote Union Territory.

- Supports Atmanirbhar Bharat and blue economy goals by positioning Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a key growth center.

- Ecological and Cultural Significance:Great Nicobar Island is a biodiversity hotspot, part of the Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve, home to unique flora and fauna. Development could violate India’s commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

-

- Poses severe threats to Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) such as the Shompen, whose survival is linked to India’s constitutional protections (5th and 6th Schedules) and international tribal rights reputation.

- Broader Implications:The project sets a critical precedent in the ongoing national debate about “development versus environment.”

-

- Poor handling could trigger legal challenges (e.g., from the National Green Tribunal) and draw international criticism.

- Being located in a disaster-prone archipelago, the project risks large-scale loss that could impact India’s national security and climate resilience efforts.

Conclusion: The Great Nicobar project embodies a conflict between national strategic interests and indigenous rights, environmental conservation, and sustainable development.

- Addressing these challenges requires transparency, genuine tribal consultation, rigorous environmental safeguards, and disaster risk management.

- Protecting the fragile ecosystem and tribal livelihoods is essential to preserving national values and ensuring ethical development.